Gatekeeping and Inclusive Leadership: The Role of Racialised Minority Gatekeepers in Promoting Equity in the Post-2020 Black Lives Matter Protests-Era

In this post blog, Fidele Mutwarasibo, Senior Lecturer and Director of the Centre for Voluntary Sector Leadership, shares insights into a paper on racialised minority gatekeepers published in 2023. The paper reflects on his experience as a racialised minority gatekeeper in the United Kingdom and Ireland and the lessons he learnt as a pracademic (scholar-practitioner) at The Open University, researching the leadership of racialised minority networks in the past five years.

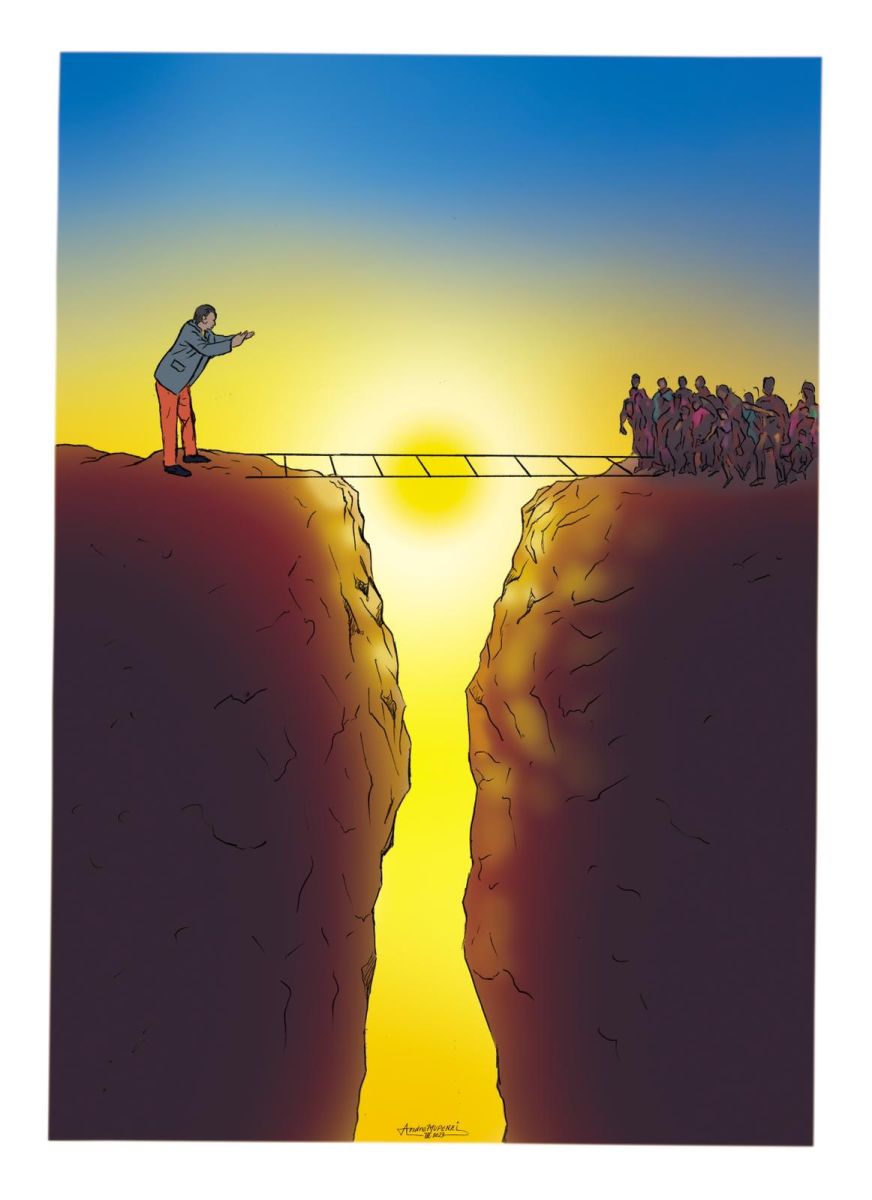

In today’s diverse societies, racialised minority gatekeepers are crucial in fostering diversity, equity, inclusivity, and belongingness. Often positioned at the intersection of various cultural and social spheres, these individuals act as bridges between racialised minority communities and mainstream institutions. This autoethnographic blog explores the unique challenges and opportunities faced by racialised minority gatekeepers, highlighting their contributions to policymaking, community leadership, and cultural preservation. By understanding their pivotal role, we can better appreciate the complexities of navigating and dismantling systemic barriers, ultimately paving the way for a more inclusive future. Furthermore, the blog unpacks the behaviour of the racialised minority gatekeepers. It raises concern about the propensity of service providers to engage and collaborate with ladder-pulling racialised minority gatekeepers without challenging their representativeness and accountability to the communities these gatekeepers claim to represent.

Gatekeeping can have both positive and negative connotations. Moreover, we enter through many gates in life and sometimes find the gates closed or accessible. The word gatekeeping is rooted in military tradition. It describes “the activity of controlling and usually limiting general access to something” (Willems, 2001; Dehghan & Wilson, 2019, p.217). The gates can be physical or non-physical. For disadvantaged communities non-physical gates can be an invisible barrier to the public but real to them. Literature suggests three types of gatekeepers – formal, comprehensive, and informal. Formal gatekeepers include the police and school staff, comprehensive gatekeepers can be found in supportive agencies or charities, and informal gatekeepers are embedded within the community and mediate the communities with the formal and comprehensive gatekeepers (Emmel et al., 2007; Wilson, 2020, pp. 463-464). This post blog focuses on the informal gatekeepers from racialised minority communities. These gatekeepers are relied upon by service providers, researchers, and other actors seeking to reach out to the communities they have difficulties accessing. Racialised minority gatekeepers are often called upon in outreach activities in many areas, including health, education, youth work, social work, housing, and research.

Calls to support service providers’ outreach in the early months of COVID-19, made me realise how I had served for many years as a gatekeeper. I have acted as an interpreter, a cultural mediator, a broker, an advocate, and a lobbyist, among other roles. The reflections in this blog are from the paper titled From the Periphery to the Centre: An Autoethnographic Account of Positionality, Practices and Behaviours of Racialised Minority Leaders (RMLs) published in 2023. As the title of the paper suggests, it is an autoethnography. Autoethnography is a “self-critical sympathetic introspection and the self-conscious analytical scrutiny of the self as researcher” (England, 1994, p. 82). In a nutshell, the blog is a reflection on my experience as a racialised minority gatekeeper and my reflections on the practices of other racialised minority gatekeepers I encountered along my life journey, especially the other gatekeepers I engaged with in the last five years.

Based on my lived experience and my observations, I developed a typology of racialised minority leaders that includes ladder-pulling, ubiquitous, self-effacing and bridge-building racialised minority gatekeepers. The typologies are covered briefly below, and a detailed review is available in the paper.

- Ladder-pulling racialised minority gatekeepers influence and control emerging leaders' (from the racialised minority communities) access to policymaking forums set up by service providers.

- Ubiquitous racialised minority gatekeepers are willing to keep open other leaders’ access route to service providers but want to remain omnipresent and maintain some control.

- Self-effacing racialised minority gatekeepers are influencers who keep open the access route to service providers to other leaders, prepared to mentor them and not overshadow them.

- Bridge-building racialised minority gatekeepers are aware of positionality as brokers and willing to act as mentors, capacity-builders, and planners for their succession.

As the outlines of the typologies suggest, gatekeeping can be positive or negative depending on the gatekeepers’ behaviours and approaches. The self-serving ladder-pulling, for example, can create barriers between the communities they claim to serve and the service providers. Ubiquitous gatekeepers can make it difficult for leaders with alternative views to access the service providers to maintain their influence. Self-effacing gatekeepers can support the emergence of other leaders and gatekeepers through succession planning initiatives, making it easy for service providers to go beyond engaging with the usual suspects. Bridge-builders do more than plan their succession; they invest in supporting and empowering community leaders. They also work on establishing lasting relations with service providers, making it easier for the latter to reach out to their communities through many gatekeepers rather than always going to the same people.

The paper has implications for both the gatekeepers and the service providers. The paper urges gatekeepers to reflect on their behaviours (especially those that limit and control access to policymaking mechanisms) and leadership practices (especially those making them the sole interlocutors for the communities they claim to represent). The paper underscores the need to invest in succession planning and community resilience. The paper reminds service providers to be open-minded about the motives of the gatekeepers who engage and collaborate with them. Furthermore, the paper reminds service providers of the need to invest in building the capacity of racialised minority networks rather than always relying on the same cohort of gatekeepers. Finally, the paper urges researchers to recognise that the gatekeepers they engage with may differ from the bridge-builder gatekeepers they seek to access communities they are researching.

References

- Dehghan, R. & Wilson, J. (2019). Healthcare professionals as gatekeepers in research involving refugee survivors of sexual torture: An examination of the ethical issue. Developing World Bioeth. 2019;19, pp. 215–223.

- Emmel, N.; Hughes, K.; Greenhalgh, J. & Sale, A. (2007). Accessing Socially Excluded People: Trust and the Gatekeeper in the Researcher-Participant Relationship. Sociological Research Online 12 (2): pp. 1–13. doi.org/10.5153/sro.1512.

- England, K. (1994). Getting personal: reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer 46, pp. 80–89.

- Willems, D. L. (2001). Balancing rationalities: Gatekeeping in health care. Journal of Medical Ethics, 27 (1), pp. 25–29.

- Wilson, S. (2020). ‘Hard to reach’ parents but not hard to research: a critical reflection of gatekeeper positionality using a community-based methodology. International Journal of Research & Method in Education 2020, VOL. 43, No. 5, pp. 461–477