Policing the First Global Financial Crisis: Remembering The 1825 Panic

Dr David Gordon Scott

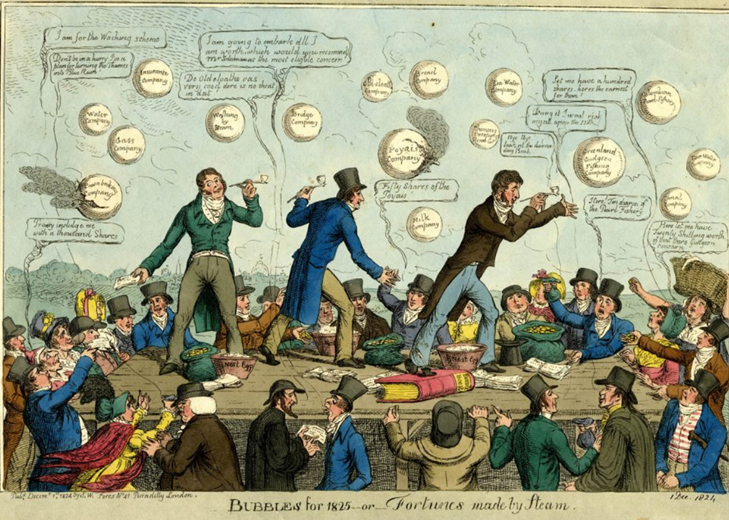

Image 1: Bubble During the Panic of 1825. Source: Investor Amnesia

The ‘1825 Panic’ stands as the most significant crisis in the history of the British banking system until 2008. It was the largest financial crisis of the nineteenth century, reflecting a massive destabilisation of the banking system.

Multiple factors contributed to the crisis, including a prior credit boom, stock market crashes, and reckless speculation in Latin/South America. The most telling feature of this financial disaster was the scale of bank failures: more than 10% of England’s Country banks went bankrupt during or shortly after the Panic, and several London banks also collapsed, greatly diminishing confidence in the financial system overall.

Although the crisis was widely recognised at the time, it has largely faded from public memory over the past two centuries. The secondary literature often refers to the 1825 financial crisis, but rarely in detail. George Eliot’s Middlemarch (published in 1872 and set in the 1830s) remains among the few sources still engaged with today that explores the lingering fears and anxieties following the Panic, as its business-class characters continue to deal with its psychological and emotional fallout. Over time, myths have emerged about the Panic, conveniently blaming ‘bad apples’ and ‘corrupt speculators’, which helps obscure the chaotic nature of early industrial capitalism and the structural frailties of the banking system, as well as downplaying the responsibility of those in power for the human suffering caused by the crisis.

The Birth Pains of Laissez-Faire Capitalism

The 1825 Panic was part of the birth pains of laissez-faire capitalism. The ideological emphasis on free markets and trade, competition-determined wages, the supposed long-term benefits of industrialisation, individual responsibility, and non-intervention in economic matters were deeply embedded in government thinking. As Lord Liverpool famously declared, nothing could be done to alleviate the crisis ‘until the trades come round’. These ideas were popularised by laissez-faire advocates such as Harriet Martineau. Politicians and supporters of laissez-faire capitalism were aware that the collapse following the Panic would cause enormous collateral damage and suffering, yet their reaction adhered strictly to free market and non-interventionist doctrine. Their focus on banking system failures was mirrored in their approach to ‘policing the crisis’, which relied on ‘law and order’ policies and legal repression.

Devastating Effects on the Working Classes

The 1825 Panic had profound repercussions for the living conditions of the working classes across England. In the wake of the financial collapse, between 1825 and 1827, there was a severe downturn in trade. In 1825 GDP was down by a staggering 4.2%. This resulted in commercial and industrial bankruptcies among the business class, as well as mass unemployment, underemployment, diminished wages, and higher food prices. These problems were compounded by a poor harvest in 1826. Financial crisis led inevitably to economic depression and distress, which in areas with traditions of popular protest resulted in uprisings, met with legal and sometimes lethal repression.

Laissez-faire ideologues like Harriet Martineau promoted above all the importance of social order and unbridled capitalist expansion. Thus, Martineau argued that the poor deserved charity only if they remained orderly, but, denied most avenues of political representation, ordinary people’s suffering could only be heard through direct action protest. In 1826, anti-starvation uprisings occurred throughout England and were suppressed by the military, with the largest taking place in Pennine Lancashire over four days in April.

Image 2: The Bank of England, South Front View in 1814.Copyright Artist: J. P. NEALE

Causes of the 1825 Banking Crisis

While boom-and-bust cycles were familiar, the crash in 1825 was unprecedented in its scale and impact. The crisis seemed to strike suddenly, with no obvious explanations, and was not foreseen as being the worst banking crisis in British history to that date. However, the seeds of disaster had been sown over preceding decades, and by 1825, conditions for crisis were present. After the Napoleonic Wars, the City of London became the world’s foremost financial market, with investors eager for quick profits through stocks and shares.

It is clear in retrospect that several factors contributed to the crisis:

A Poorly Coordinated Banking System

The English banking system in 1825 was comprised of the Bank of England, several London banks, and many Country banks. The Bank of England, still privately owned, had divided loyalties between generating profit for stockholders, managing government finances, and supporting commercial banks. The London banks were established for-profit enterprises that supported the Country banks, which had grown rapidly as industrial capitalism expanded. By 1815, there was a country bank within 15 miles of anywhere in England. The lack of coordination, competing interests, and profit motives meant bankers could act in contradictory ways during times of crisis.

Structural Vulnerabilities of Country Banks

Both licensed and unlicensed Country banks had structural weaknesses. The Bank of England held a monopoly on joint-stock banking, while the Country banks were numerous but small, with limited reserves and restricted partnerships. Their lack of diversification and reliance on correspondent London banks made them vulnerable to collapse. Many interventions after the Panic focused on changing how Country banks operated, including joint-stock holdings and unlimited liability for losses.

Overuse of Country Bank Notes

In 1824 and 1825, Country banks over-issued promissory notes. In these years the number of stamped notes doubled compared to 1822, following government permission to increase note circulation to stimulate growth. In regions like Lancashire and West Riding, Country bank notes were widely used for wages and dominated local currency. The extension of currency from 1822 to 1825 encouraged speculation, but when the banking system crashed, these notes became nearly worthless, creating mass panic. Although Lancashire banks avoided mass collapse, working people and businesses suffered greatly.

Bank of England Policies during the 1822–1824 Boom

Monetary policies by the Bank of England, including eased credit restrictions, low interest rates, and a 25% increase in note issues between February 1822 and February 1825, spurred a super-charged boom. The Bank also reduced interest rates, prompting speculators to seek higher returns abroad. Increased overseas investment and trade ultimately depleted the Bank’s gold reserves, and the resulting credit and speculative boom proved unsustainable, with many foreign loans turning out to be poor investments and triggering a crisis of confidence.

Corruption and Speculation

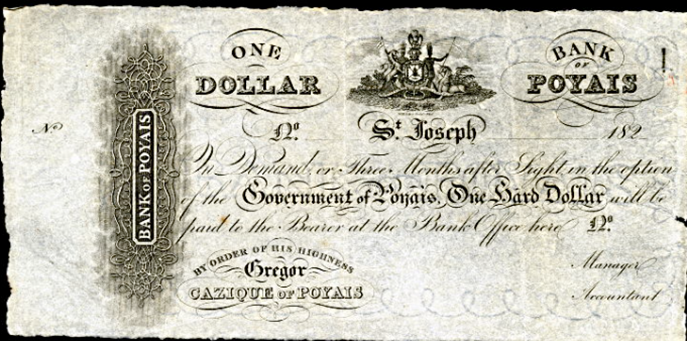

High-risk ventures in South and Latin America and widespread corruption were further cited as causes. South and Latin American markets became accessible to British investors after the Napoleonic Wars, offering higher interest rates and attracting speculative investments. Many loans were poorly underwritten, and by 1824–25, £42.9 million in capital was raised for such investments. The collapse of faith in these risky loans in 1825 burst the speculative bubble, with defaults creating strains on the banking system. The infamous ‘Poyais scandal’—a fraudulent scheme by Gregor MacGregor who in effect invented a fake country—epitomised the excesses and corruption of the period, leading two London banks to bankruptcy and hundreds of working-class emigrants to financial ruin and death.

Image 3: One Dollar Note, the Bank of Poyais. Source: Historic.Uk

The 1825 Panic: Timeline and Events

Share prices peaked in January 1825, but soon news of poor performance of Latin American loans and reckless speculation caused concern. Warning signs appeared by the spring, and in April the London stock and bond market crashed, immediately affecting collateral value, causing bankruptcies, and slowing trade. The crisis deepened throughout 1825, with Latin American bonds halving in value and country banks accruing enormous debts. Nervous customers began withdrawing deposits and converting them to gold and silver. By September, multiple banks were on the brink of failure. The government introduced deflationary policies, worsening the domestic money supply and deepening the crisis. The losses from South / Latin American investments had spread into the broader business world, and tighter money supply increased anxiety and further eroded confidence.

Manufacturers began selling goods originally intended for domestic customers in foreign markets at reduced prices, but this did not resolve the situation. By autumn, banks began to fail, starting in Devon and the West of England, with a prominent Yorkshire bank collapsing in November. A series of runs threatened many more banks with imminent failure.

The 1825 Panic peaked in December. The banking system seized amid widespread loss of confidence, with crowds gathering outside banks. On 12 December 1825, the collapse of Pole, Thornton & Co. triggered the downfall of forty-three correspondent country banks. By 14 December, fear of further bank failures was rampant. Runs on several London banks and intense pressure on the Bank of England, especially between 11–18 December, created heightened demand for cash, banknotes, and gold. By 17 December, the Bank of England had exhausted its supply of £5 and £10 notes and began circulating £1 notes for the first time since 1821. The Rothschilds brokered an emergency consignment of silver coins and gold sovereigns from the Bank of France to alleviate the currency crisis.

Although Peru only formally defaulted in April 1826, months before most speculators had realised their losses. Six London banks, and many more Country banks, failed during the crisis, most having financed risky South or Latin American loans.

Bank Failures and Systemic Collapse

The fallout from the Panic is illustrated in reports from the 1832 Committee on the Bank of England Charter. Banks such as Perring & Co. (victims of the Poyais fraud), Everett & Co. (loan defaults in Peru), and Fry and Chapman (Peruvian and Mexican debt), along with others like Goldschmidt and Barclay, Herring, Richardson & Co., and Thomas, Jenkin & Co., failed between February and April 1826. Many banks suspended payments or collapsed entirely—seventy-three in total. Thirty Country banks were bankrupted in December, with thirty-three more in the first quarter of 1826. Many more faced ongoing difficulties and sought assistance from the Bank of England, which provided £3 million in emergency funds. The damage extended beyond banking: the economy was days away from total collapse in December 1825, and the shockwaves persisted for decades, leading to one of Britain’s worst depressions.

Consequence: A Deep Economic Depression

The 1825 Panic led to a collapse in business confidence, disruption of the payment system, transfer of domestic trade abroad, suspended production, inflation, soaring unemployment, near-starvation for the poorest people in society, mass disorder and social unrest, and hundreds of bankruptcies. The depression had four interlocking characteristics:

Collapse in Confidence

Confidence in the financial system evaporated. Bank of England notes, backed by the government and gold, were still valued, but Country Bank promissory notes were now seen as worthless. In places like Manchester, trade ground to a halt as people rushed to exchange notes for gold, and provincial notes became little more than wastepaper. Bank failures destroyed trade locally and nationally.

Paralysis of Markets and Trade Depression

Many areas relied on Country Bank notes as currency, and their collapse led to immediate cashflow problems. Surviving banks became cautious, and credit supply nearly stopped. The value of exported cotton manufactures dropped by 20%. Manufacturers, battered and paralysed, halted production, unable to purchase materials or pay wages. Payments to companies and individuals were suspended, leaving tens of thousands unemployed.

Unemployment and Lower Wages

Trade collapse and suspended production led to mass unemployment. Those still employed saw wages slashed, with weavers’ wages dropping by a third. The suppression of £1 notes in 1826 further reduced money in circulation, worsening wage reductions and destitution for workers.

Commercial Bankruptcies

Bankruptcies soared in the last quarter of 1825 and throughout 1826, more than doubling the average annual rate for 1822–32. Bankruptcies rose by 150%, from 999 in 1825 to 2,590 in 1826.

Trade became toxic and the economy melted down, only starting to stabilise in summer 1826. The immediate fallout from the 1825 Panic lingered into the following year. As one local historian wrote in the 1890s, it was a sad period for the working classes, with daily news of business failures, low wages, diminished employment, and widespread destitution and hunger.

Policing the Crisis

The government’s response to the 1825 Panic reflected its commitment to laissez-faire ideology. Swift action was taken to restore the banking system and market confidence, but little sympathy was shown for ruined capitalists (deemed reckless) or for workers and families devastated by depression. While there was some sympathy for the unprecedented distress for the law-abiding, especially given the poor harvest of 1826, the main policies deployed were those of law and order, reflecting the moral stance of the ruling elite, and falling short of the codes held by the populace.

Image 4: Policing The Crisis book front cover 1978 edition: Copyright Macmillan Press

Banking Reforms

The banking crisis was at its worst in late 1825. Conflict between the government and Bank of England over addressing the financial meltdown led to Lord Liverpool considering retirement in February 1826, threatening government dissolution. In the end, The Bank of England advanced half a million in security, and Liverpool introduced two new bills. The Banknote Act (22 March 1826) imposed new restrictions on note issuance, including the notorious Country bank promissory notes, which were to be withdrawn by 1829. The second bill authorised multiple-partnership and joint-stock banks outside a 65-mile radius of London, permitted separation of ownership and control, managerial hierarchies, transferable shares, and unlimited liability. The Bank of England was also allowed to establish provincial branches, diversifying the banking system.

The Bad Harvest and Corn Laws

The economic depression was much deeper than expected and was exacerbated by a poor harvest in 1826. Drought in July and August reduced yields of oats, potatoes, and pulses by a third, hitting the poorest hardest. Oat prices rose dramatically. Plans to open corn deposits commenced on 29 August 1826, and application of the corn laws was amended to allow the release of peas and beans on 1 September. The government intervened to avert famine but had been reluctant to intervene economically during the previous eight months of catastrophic impact from the Panic.

Government Inaction and Rhetoric

There was a stark difference between government rhetoric and reality. While the message was one of solidarity—asserting that the wealthy would help the poor and share their last shilling—the true priority was the health of the market and capitalist accumulation, not the reduction of suffering. Dissent and those who jeopardised the financial system were not tolerated. Ruined speculators were blamed for the collapse and rendered ineligible for sympathy.

A Law-and-Order Ideology

In the early Nineteenth century, Economic distress and social unrest were managed through legal repression rather than welfare. Economic policy in the pre-police age was mainly about maintaining order and securing optimal conditions for capitalist accumulation. Protests and industrial action breached these cardinal rules of the laissez-faire doctrine. Ministers feared the coincidence of high bread prices and urban unemployment but refused to alleviate hams. Industrial stagnation, popular uprisings, and loom-breaking in 1826 were met with military force.

The widespread disorders of 1826 arose from unemployment, poverty, and starvation, and those charged with repression knew permanent security could not be achieved until economic causes of unrest were addressed. In fact, the failure of government to provide any systematic economic intervention to relieve distress and its exclusive recourse to law-and-order interventions as its way of ‘policing the crisis’ of laissez faire capitalism then paths the way to the circumstances that resulted in the killing of anti-starvation protestors at Chatterton on 26th April 1826, one of Britains hidden massacres that Open University research is also helping to bring back into public memory.