The Names that Did Not Appear in the Newspapers: Under 5 Child Deaths in Pennine Lancashire, April 1826- March 1827

David Gordon Scott and Kate Hurst

Image: 1826 Anti-starvation protest coffin. Source: Photo copyright author

200 years ago, England was rocked by a great financial crisis – what has become known as the 1825 Panic. The damage done to businesses and the overall economy was closely monitored and recorded in various statistics at the time. Newspapers and reviews, such as the Annual Register, provided extensive details of bankruptcies and other financial woes. Less visible though was the enormous negative impact of the 1825 panic upon the lives of ordinary people. It was, however, widely acknowledged that the resulting great depression of 1825-7 created profound social distress and, at least in local newspapers, the extent of regional unemployment, diminished wages and higher food prices were reported. Further, to ensure their voice was heard in a moment of great social distress, there were popular protests and risings across the country in 1826, with perhaps the most extensive being in Pennine Lancashire in April of that year. These protests were, albeit in a negative way, also covered extensively in the newspapers at the time, as were the names of the six reported dead at the Chatterton massacre.

Yet the avoidable and premature deaths of ordinary people, and especially young children – in other words the deadly human consequences and social harms of economic turbulence – were only rarely recorded or reported in the newspapers. Not only are such premature and avoidable deaths now long forgotten. They barely have been remembered at all. The social harms of an economic depression may not be fully evident in death rates of adult populations for maybe up to two years after the event (meaning that we would anticipate the legacy of the 1825-7 economic depression to be felt as late as 1829). Young children, though, are less resilient than adults and are likely to feel the brunt of a major economic catastrophe sooner, perhaps within weeks and months. Our focus is on statistics accumulated from the 58 parish records on avoidable and premature deaths of young children in Pennine Lancashire only a few months into the great 1825-7 economic depression. Our timeframe for data analysis is thus from April 1826 to March 1827.

Method: Giving Voice to the Otherwise Voiceless

This article begins by listing the number of children under 5 buried in Pennine Lancashire during the specified year as recorded in 58 parish records. It is important to note that the recorded causes of death do not give malnutrition or starvation as the reason for the death. In many instances, the reasons for the deaths are not given at all.

Our method of analysis of the data on child deaths involved in person and online counting of the Lancashire Parish records. We note that there was a difference between the recording of the deaths in different parish records and that not all records were complete in terms of giving names, ages or causes of death. The data set therefore remains incomplete, but we are confident that our transcribed data is the most comprehensive and reliable in existence. Our method is unique as it uses parish burial records to represent those who otherwise have no voice.

Image: Walmsley Chapel. Photo Copyright author

The second part of the article focuses on naming and remembering some of these children. We highlight ten bereaved families in Pennine Lancashire, all of whom lost at least one child under the age of 5 during the period April 1826 and March 1827. Collectively these accounts reveal the suffering of these families and indicate a concentration of multiple child mortality, giving voice to the otherwise voiceless.

Under 5 Child Deaths, April 1826-March 1827

The numbers of under 5 deaths (and also any number of deaths that were recorded as children but had no age identified) in each of the 58 parish records where data was available are detailed below.

TABLE 1 Under 5 Deaths in Pennine Lancashire, April 1826 – March 1827

| PARISH NAME | Under 5 Deaths Recorded April 1826 - March 1827 | Death recorded as a child, but no age given or age unclear |

| 1. Chorley, Weld Bank RC | 12 | - |

| 2. Downham, St. Leonard | 5 | - |

| 3. Edenfield Chapel | 13 | - |

| 4. Goodshaw Booth, St. Mary | 8 | - |

| 5. Pleasington, St. Mary and St. John RC | 1 | - |

| 6. Tockholes, St. Stephen | 1 | - |

| 7. Holcombe, Emmanuel Chapel | 77 | - |

| 8. Great Harwood, St. Bartholomew | 38 | - |

| 9. Bamford Independent Chapel, Heap | 1 | - |

| 10. Chorley, St. Laurence | 2 | - |

| 11. Clitheroe, St. Mary Magdalene | 47 | - |

| 12. Bury, Union Street Wesleyan Methodist | 17 | |

| 13. Over Darwen, St. James | 35 | - |

| 14. Newchurch in Rossendale, St. Nicholas and St. John | 58 | - |

| 15. Bacup, St. John | 26 | 1 |

| 16. Darwen, Belgrave Independent | 2 | - |

| 17. Bacup, Ebenezer Baptist, Doals | - | 21 |

| 18. Blackburn, St. Mary the Virgin | 282 | 3 |

| 19. Longholme Wesleyan Methodist, Rawtenstall | 2 | - |

| 20. Ramsbottom, Park Street United Reformed/Methodist | 2 | - |

| 21. Accrington, St. James | 39 | - |

| 22. Church Kirk, St. James (Accrington) | 44 | - |

| 23. Altham, St. James C of E | 20 | - |

| 24. Bury, St. Mary C of E | 215 | - |

| 25. Haslingden, St. James | 161 | - |

| 26. Haslingden, King Street Wesleyan | 2 | - |

| 27. Darwen Wesleyan Chapel | 3 | - |

| 28. Darwen, Independent Chapel | 14 | - |

| 29. Bury, Central Wesleyan Methodist | 21 | - |

| 30. Blackburn, St. John the Evangelist | 12 | - |

| 31. Blackburn, Islington Baptist Chapel | 9 | - |

| 32. Blackburn, Chapel Street Independent | - | 28 |

| 33. Blackburn, St. Paul | 57 | - |

| 34. Blackburn. St. Peter | 40 | - |

| 35. Bacup, Mount Pleasant Wesleyan Chapel | - | 12 |

| 36. Whalley, St. Mary and All Saints | 31 | - |

| 37. Samlesbury, St Leonard the Less | 15 | 2 |

| 38. Rivington Unitarian | - | 1 |

| 39. Langho. St. Leonard | 8 | - |

| 40. Tottington, St. Anne | 22 | - |

| 41. Blackburn, St. Alban RC | 4 | 2 |

| 42. Mitton, All Hallows | 4 | 1 |

| 43. Bury, St. John | 43 | - |

| 44. Unsworth, St. George | 6 | - |

| 45. Heywood, St. Luke (partial 1827) | 97 | - |

| 46. Brindle, St. James | 16 | - |

| 47. Turton, St. Anne | 33 | - |

| 48. Accrington, Union Street Wesleyan | 3 | - |

| 49. Rivington Anglican | 21 | - |

| 50. Grindleton, St. Ambrose | 42 | - |

| 51. Bacup, Wesley Place Wesleyan Methodist | 12 | - |

| 52. Balderstone, St. Leonard | 6 | - |

| 53. Salesbury, St. Peter | 3 | - |

| 54. Hoghton, Holy Trinity | 3 | - |

| 55. Heapey, St. Barnabus | 2 | - |

| 56. Grindleton, Rodhill Non Conformist | 3 | - |

| 57. Brindle, St. Joseph RC | 5 | 23 |

| 58. Marsden, Crawshaw Booth Quaker | 2 | - |

| TOTALS | 1647 [58 parish records] | 94 [Four additional parish records – 10 with data in total] |

| The figure could be as high as 1741 of children under 5 in 12 months April 1826-March1827 | ||

There were 1647 recorded deaths of children under the age of 5 in this 12-month period from 58 parish records of Pennine Lancashire (of which 53 of the 58 held details with ages and the other 5 child deaths with no age stipulated). The actual figure of under 5 child deaths though could be higher. There are three reasons why this could be the case.

First, there were well-made claims by commentators in the 1840s that even in what appear to be complete parish records may have underestimated the actual number by perhaps as high as 20% of the deaths. We have not factored this into our calculations in this article, but we recognise that potentially the figure could be several hundred higher than what we have unearthed in the parish records.

Second, when researching the parish records not all data was available. We note that we did not find evidence of any names of under-5-child-deaths in 16 further registers that we analysed (Total: 74 registers). This was sometimes down to the data being incomplete, but also because on occasion the area covered by this parish in 1826-27 was very small.

Third, in the parish records we also found several records that indicated a child had died but no age is subsequently given. In 10 of the 58 parish records we found in total that 94 deaths had been recorded as children, but no age was given. We therefore note that whilst we do not know if any, or indeed all, of these deaths were of children under 5, it is possible that our figure of 1647 needs to be increased by 94 so that the number of under 5 child deaths is recorded as 1741. However, as it seems impossible to now verify the ages these additional deaths, we retain our original findings of the1647 figure.

Image: Haslingden Church. Photo copyright author

Saying Their Names

But who were these 1647 children? It is not possible here to explore all of the names of those who died (we will name these in full elsewhere in 2026), but we do feel that it is important to name some of the dead and thus add a little more meaning to the overall data. A number, no matter how big is difficult to relate too. A series of names reminds us that they were human beings.

Below we have chosen only 10 families from Pennine Lancashire that lost at least one child under the age of 5 in the period April 1826-March 1827. Where information is available we provide brief details of locations, baptisms, their parents, their parents occupations, other siblings and causes of death. We provide all the information that we believe is available about these children. All the 10 families discussed experienced multiple cases of child deaths and as such we do not restrict our discussion here to only children under 5. Yet these families are indicative of the terrible woes facing so many at the time. To our knowledge, none of these names appeared in the newspapers or have previously entered public memory.

The Catterall Children: Grace and Mary

Joseph Catterall (a weaver) and Jenny (or Ginny) Halliwell, were both were illiterate, and residents of Blackburn when they married on 25 August 1823, at St. Mary the Virgin’s Church, Blackburn. Their daughters Grace (born 30 January 1824) and Mary (born 28 April 1826) were baptised at St. Paul’s Church; unusually, the causes of their death were listed. Grace’s death, on 27 October 1826, was attributed to smallpox. Mary, who was born on 28 April 1826 and baptised on 15 May, was just over ten months old when she died from consumption on 19 March 1827.

The Markland Children: Thomas and Caroline

The date and location of printer William Markland’s marriage to his wife Isabella is uncertain, but baptisms registers for St. Mary’s Church, Goodshaw show that they lived in the village in January 1819, and had three children - Thomas, Caroline and Eleazer - before their fourth child, Onias, was born at Folly Clough, in early 1825. Although Pigot’s Directory for 1828-1829 clearly states that calico printers Grimshaw and Brooks were established at Love Clough (pg.257), and that cotton manufacturers John Kay, and Crankshaw and Pickup each had establishments at Goodshawfold (pg.258), this was insufficient to preserve the lives of all six Markland children. On 15 July 1826, Caroline, nearly five years old, was buried at St. Mary’s Church, Goodshaw; eight weeks later, on 10 September, the funeral of her eldest brother Thomas (aged seven) was held.

The Bentley Children: Richard (and later Betty, Adam and David)

On 3 January 1825, John Bentley married Margaret Bickerstaff at St. Bartholomew’s Church, in Great Harwood, between Blackburn and Whalley. The couple lived at Lowertown, and had seven children over the next eighteen years, but parish registers lay bare the stark reality of their experience of parenthood. Their eldest child Richard lived for eight days, and was buried on 18 March 1827. Although this is the only death that falls within our time frame, tragedy was to strike the family again. Less than a year later, the funeral of their three week old daughter Betty took place on 16 March 1828. Adam, their fourth child, died almost ten weeks after his baptism on 15 May 1831, and a younger son - David - was ten days old at his burial on 23 September 1840. Throughout this period, John Bentley was described as a calico printer, with one exception; his son John’s baptism record indicates that he was employed as a plasterer in February 1829.

Image: St Nicholas, Newchurch. Photo copyright author

The Ashworth Children: John and Joseph

The registers of Pennine Lancashire’s non-conformist chapels often contain fewer entries than their Anglican counterparts, simply because these religious communities tended to be smaller; for example, 673 burials were recorded at St. James’ Church, Over Darwen between January 1820 and December 1830, whereas the local Wesleyan Methodist Chapel recorded only 332 burials during the same period, yet the latter register is still capable of revealing heartbreaking stories of child loss. Robert and Betty Ashworth’s son John lived for just nine hours prior to his burial on 7 August 1826; it is unlikely that his mother was present at the funeral so soon after childbirth, but she may have attended the interment of her three-year-old son Joseph a month later, on 12 September 1826.

The Wensley Children: Catherine and Lettice

On 14 June 1826, six month old Catherine Wensley, the daughter of Edmond and Catherine of Blackburn, died from “consumption”; on 30 November, 1826, an elder sister - Lettice, aged two - died from smallpox.

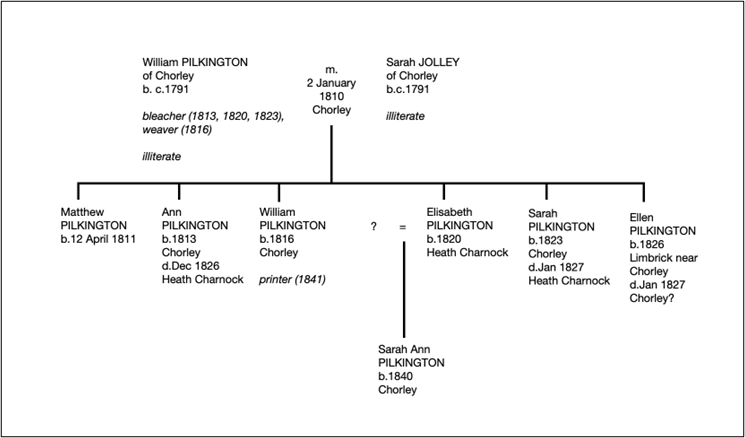

The Pilkington Children: Ann, Sarah and Ellen

Faced with economic difficulties, it is interesting to wonder whether Lancashire’s textile workers faced Christmas 1826 with a determination to enjoy whatever aspects of the season they could, or whether it was merely another reminder that any traditional treats were completely unaffordable. In Chorley, Christmas may have reminded William Pilkington, a bleacher, and his wife Sarah Jolley that their seventeenth wedding anniversary was approaching, on 2 January 1827. Baptism registers for St. Laurence’s Church show that they had six children, aged between fifteen and four months, but the burial registers show a different view of their lives. On 21 December 1826, their thirteen year old daughter Ann was buried; three year old Sarah followed on 7 January 1826, and seven days later, another funeral was held for their youngest child, Ellen (aged six months).

The Sandham Children: The Twins Priscilla and Margaret (and earlier Ann)

The registers of St. Nicholas and St. John, at Newchurch in Rossendale, also give insights into the life of Lancaster-born woolcomber John Sandham. John married Ruth Nuttall on 28 June 1819, at St. Mary’s Church, Bury, just three months before their daughter Mary was baptised at Newchurch in Rossendale; by then, the Sandhams lived on Clough Lane. Parish records show that the couple had a further eight children over the following eighteen years, but three did not survive infancy. Their second daughter Ann was buried on 29 June 1824, two years and seven months after her baptism. Less than eighteen months later, on 13 November 1825, when the family were living at New Hall Hey, twins Priscilla and Margaret were christened, but neither survived until their second birthday. Priscilla was buried on 23 June 1826, whilst Margaret’s funeral took place on 2 February 1827.

The Partington Children: George and Thomas

On 2 May 1824, spinner James Partington of Brooksbottoms and his wife Susannah (sometimes spelt Susan) had their son George baptised at Park Independent Chapel, Walmersley. Two days after George’s burial at the same church on 20 August 1826, his brother Thomas’ baptism record described their father as a mechanic, but his life would be even more brief. His funeral took place on 20 February 1827.

Image: Holcombe Church. Photo copyright author

The Wild Children: Mary and Richard

In some instances, the Newchurch in Rossendale registers offer little more than snapshots into child loss during the 1820s. On 15 January 1827, when four-year-old Mary Wild was interred, the address of her parents James and Ann was simply “Workhouse”; three days later, their son Richard - aged six - was also buried, and the family’s address was unchanged. This might imply that the Wilds had moved into the area and become destitute, but alternatively, they may have moved away from the Rossendale area, only to be “repatriated” to their home parish (or, at least, to James’ home parish) when their situation became desperate. There is no evidence that James and Ann married at Newchurch, that any of their children were baptised there or that they remained in the area, yet the burial records of Mary and Richard, only three days apart, are enough to convey the heartbreak suffered by the family during a single week in early spring 1827.

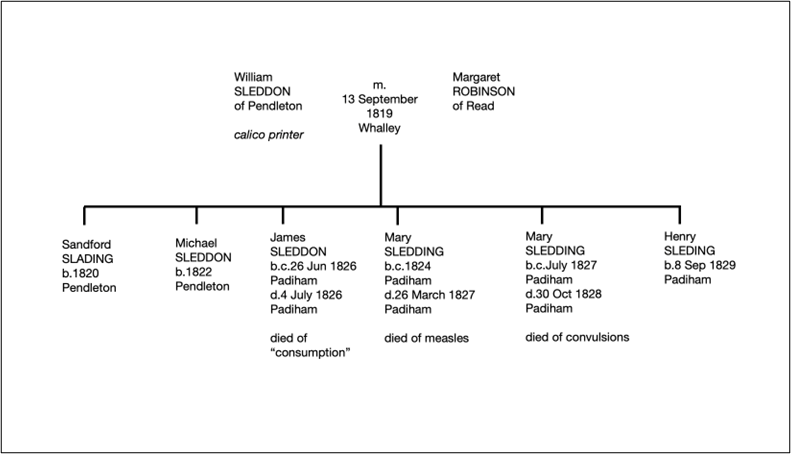

The Sledding Children: James, Mary and Mary

The Sledding (or Sleddon) family’s story began on 13 September 1819, with the marriage of William Sleddon of Pendleton and Margaret Robinson of Read, at St. Mary and All Saints Church, Whalley. Baptism records for their eldest sons Sandford (9 January 1820) and Michael (3 February 1822) show that - initially - the family lived in Pendleton, on the north-western side of Pendle Hill, where William was employed as a calico printer. Between the spring of 1822 and the summer of 1826, they moved to the south side of Pendle. Settling in Padiham, the Sleddings had at least three more children. Burial records for St. James’ Church in nearby Altham show that four-day-old James died from consumption on 4 July 1826, and Mary (aged three) died from measles on 26 March 1827, whilst the later death of a younger daughter - also named Mary - on 30 October 1828, was attributed to convulsions; her age was given as one and a quarter years.

Raising Awareness and Remembrance

The above data and stories of 10 bereaved families who experienced the loss of at least one child under the age of five between April 1826 and March 1827 is just the tip of the iceberg. The parish records are filled with literally hundreds of similar stories. This archival research is ongoing, with further findings to report in 2026/7, but it is important to understand the devastating social harms and deadly consequences of the social conditions in Lancashire in the 1820s, something that the 1825 Panic only made worse. Thousands died of food poverty and hunger in the years that followed. Young lives were lost before they barely had a chance to begin. Historians have an ethical responsibility to raise awareness of the human consequences of economic and social harms and ensure that tragic tales of loss of ordinary people are not forgotten. The lives of everyday people and the loss of their children is just as important as those considered newsworthy. In the name of dignity, it is important to ensure we continue to know and say the names of the dead, including those that did not appear in the newspapers. It is one important way of giving voice to the otherwise voiceless.