Diethylstilbestrol (DES) 2025: Survivors Speak, Parliament Listens, but Will Government Act?

In the wake of relentless survivor testimony and media investigation – led by ITV News (20th February, 13th March, 9th April, 1st May, 15th July, 17th July and 23rd July 2025) - Diethylstilbestrol (DES) has re-emerged in the national conversation with force. Once hailed as a ‘wonder’ drug and now recognised as one of the most devastating pharmaceutical failures in UK history, DES has left behind not only damaged lives but a damning legacy of regulatory negligence. In the UK, DES was prescribed under various brand names, including Stilbestrol, Domestrol, Estrosyn, and desPLEX — making it more difficult for many to recognise their exposure or understand the risks. As the UK government begins to respond — under pressure from survivors, the media, and a growing number of MPs — the question remains: will it act with the urgency and accountability this injustice demands? This was not just negligence. It was abandonment — a systemic betrayal of trust.

Image Credit: Created using Canva's Dream Lab by Sharon Hartles

Buried Warnings, Enduring Harm

From the moment Diethylstilbestrol (DES) was first synthesised in the UK in 1938, its development and dissemination were deeply entwined with government policy. Created by Sir Edward Charles Dodds and his team through publicly funded research, DES was not patented — in line with UK government policy requiring that state-sponsored discoveries remain freely available. This meant any pharmaceutical company could manufacture and market the drug cheaply, without oversight, commercial monopoly, or central accountability. The public paid for its creation — but no one was appointed to ensure its safe use. If everyone was allowed to profit, who exactly was meant to protect the public?

Early Scientific Warnings — Ignored

This inaction is not excused by ignorance. British scientists, including Michael Shimkin, Hugh Grady, and Solly Zuckerman, had by 1940 published studies showing that DES caused mammary tumours in mice. These warnings were neither fringe nor unpublished — they were credible, peer-reviewed (Shimkin & Grady, 1940; Zuckerman, 1940), and accessible to UK health authorities of the time, including the Ministry of Health. But no precautionary steps were taken — not even to limit experimental use in vulnerable populations such as pregnant women. This early regulatory failure laid the groundwork for decades of official neglect. A lack of oversight is not neutral. It is a form of complicity. This was not just a gap in regulation — it was a case of state abdication.

DES, Miscarriage, and Oversight Failures

Although DES was never patented, its later shift in use from treating menopausal symptoms to preventing miscarriage should have triggered formal re-evaluation. But in the UK, there was no formal, centralised drug approval process at the time. The 1941 Pharmacy and Medicines Act focused largely on regulating advertising and the sale of patent medicines, not on licensing or scientific scrutiny. This allowed doctors to prescribe DES based on clinical judgement or pharmaceutical influence, but without formalised approval from a central body.

Faulty Evidence, Followed Blindly

In the United States, DES began to be prescribed to prevent miscarriage following early clinical studies conducted at Harvard University in the late 1940s. These trials claimed DES improved pregnancy outcomes — but crucially, they lacked control groups, a basic standard of scientific validity even in the 1940s. Despite this, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved DES for miscarriage prevention in 1947. In the UK, there was no equivalent evaluation or authorisation — yet DES was similarly adopted for pregnancy, driven more by professional emulation than by robust evidence. Once again, the UK’s regulatory blind spot allowed widespread use without due diligence.

Mounting Harm, Continued Silence

As DES prescriptions accelerated throughout the 1940s and 1950s, no UK-led follow-up studies were commissioned. When the pivotal 1953 Dieckmann trial in the United States concluded that DES was ineffective — and potentially harmful — UK health authorities remained silent. In the 1960s, UK clinicians began observing reproductive abnormalities in DES-exposed daughters, but still, no national review or clinical guidance followed. Not even the creation of the Committee on Safety of Drugs (1963–1968), or its successor, the Committee on Safety of Medicines, spurred meaningful re-evaluation. The pattern of institutional regulatory neglect had become deeply entrenched.

A Delayed and Incomplete Response

When the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning in 1971 linking DES exposure to vaginal cancer, the UK waited until 1973 to issue its own guidance — and even then, failed to fully withdraw the drug. DES continued to be prescribed into the 1980s, often in private clinics, without informed consent or adequate risk disclosure. ITV News found no evidence that DES was ever formally withdrawn in the UK, despite claims by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) that doctors were warned in May 1973 — and no record of that warning letter exists. This prolonged use was not driven by scientific uncertainty, but by political unwillingness to challenge entrenched pharmaceutical practices. The result was a systemic regulatory failure that prioritised institutional convenience over public protection.

A Failure of Regulation, A Failure of Responsibility

As DES prescriptions escalated, the UK government made no effort to commission follow-up studies, issue public warnings, or restrict access — even as international evidence of harm mounted. Despite the drug’s publicly funded origins, there was no public oversight and no meaningful accountability. Dr Sonia Macleod, a pharmaceutical safety expert at Oxford University, told ITV News: “There are clear indications that more could have been done by the regulators… If we are not doing at least as much as the [U.S.] FDA was doing to warn people, then why not becomes the question. And if there’s no good reason, then it’s that the regulators weren’t doing enough — and if the regulators, who are government bodies, weren’t doing enough, then yes, compensation should flow from the government.” “I think women have been hugely failed in the UK — particularly because this was a drug developed with government funding. There must be accountability and responsibility… There should also be recognition and an apology.” Her statement crystallises the fact that this was not just a medical failure — it was a regulatory one.

They Said It Was Just Routine

Susan Miller was given DES in 1975 to suppress her breast milk — two years after the UK government claimed doctors had been instructed to stop prescribing it. She is now undergoing treatment for aggressive breast cancer. “I was lied to all those years, and said it’s fine — but it’s not fine,” she told ITV News. Speaking about the urgent need for awareness and cancer screening, she added: “If they don’t get screened, they’re walking round with timebombs in their breasts because they don’t know.” Hers is one of hundreds of similar stories, all pointing to a pattern: routine administration of DES, often without informed consent, and with lifelong consequences.

Still Prescribed, Still Paying the Price

Mary Jarman received DES in 1977, again to suppress breast milk — years after mounting scientific warnings. She later underwent emergency breast surgery and, in her 40s, was diagnosed with cervical cancer. She expressed frustration that the drug remained available even after evidence of harm. “If it was a drug that nobody should have had... and they realised what it was doing... that should have really stopped it,” she explained to ITV News. “When they find out some kind of medicine is wrong... it should just come off the market completely.” These are not isolated cases — they are a symptom of a systemic failure.

A Child Forced Into Survival

Charly Laurence was just nine when doctors removed her uterus. “They told me I wouldn’t be able to have children. I didn’t really understand it then — but I cried a lot,” she shared with ITV News. Charly believes her cancer diagnosis was directly caused by DES her mother was prescribed during pregnancy. She has since gone on to raise awareness — and raise twins, thanks to surrogacy. Her lived experience is emblematic of the DES legacy: a drug whose damage didn’t stop with the original prescription, but continues through lost fertility, broken bodies, and unanswered questions.

More Than a Handful of Cases

ITV News has now spoken to dozens of women affected by DES: Ann Andic, Pauline Elliott, Suzanne Massey, Jan Hall, Beth Morillo-Hall, Hannah Windle-Hall, and Michelle Cowen, and many others. Some were given DES well into the 1980s. Their stories, long ignored, reveal a pattern of multigenerational harm — and a healthcare system that failed to inform, protect, or follow up.

A Growing Body of Evidence

These testimonies are reinforced by new data. A landmark European study published on 28th May 2025 tracked over 12,000 women exposed to DES in utero. It found:

- A tenfold increase in vaginal cancer, including clear cell adenocarcinoma

- Persistent elevated risk among women aged 60–69 — many of whom no longer qualify for routine cervical screening

Researchers concluded: “Screening for vaginal cancer should be extended beyond age 60.” Yet the UK government has yet to guarantee such a programme — despite decades of evidence, and mounting survivor demands.

Government Starts to Shift

ITV’s investigation prompted official acknowledgment. On 11th April 2025, Health Minister Stephen Kinnock confirmed that the government would be “bringing forward... proposals on how we might investigate it further.” Momentum has grown since. On 15th July 2025, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Wes Streeting publicly signalled openness to further action, stating: “I’m certainly open to looking at that — it’s one of the many things the government is looking at in light of ITV’s investigation.” This cautious openness has not satisfied campaigners. Many say it does not reflect the scale of harm nor the urgency required.

Wesley Streeting © House of Commons. Licensed under CC BY 3.0. Text added.

One Family’s Ordeal Becomes a National Flashpoint

Jessica Toale MP first became aware of the injustice surrounding DES after hearing her constituent Jan Hall’s account — shared publicly for the first time in an ITV News investigation. That broadcast laid bare the generational harm DES has caused and the state’s continued silence. Jan’s mother, Rita, died of breast cancer at just 32. Jan herself developed cervical cancer in her twenties. Her daughters now face fertility and gynaecological issues. “Hearing Jan’s story – and the pain this drug has caused to her, her mother, and now her daughters – brought home the human cost of DES,” said Toale. “This is not just a historic issue. Families are still suffering, and many don’t even know they may be at risk.” She added “At a time when you're pregnant and you're about to have a baby, it should be one of the most joyous times in your life. And then to find out so many years later that something you were prescribed — that was meant to help you — has actually harmed you and your family.”

Photo: Jessica Toale © House of Commons / Laurie Noble. Licensed under CC BY 3.0. Text added.

From Personal Testimony to Political Action

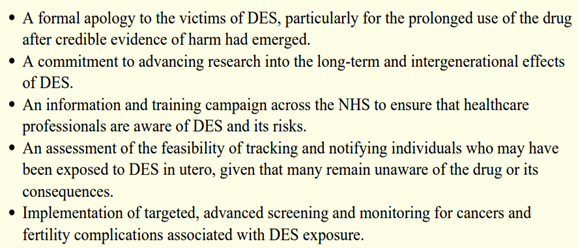

Moved by Jan’s account and determined to act, Toale has since led a cross-party campaign in Parliament. On 22nd July 2025, she and 35 other MPs — including Layla Moran, Dawn Butler, Rosena Allin-Khan, Clive Lewis, Caroline Lucas, and Barry Sheerman — wrote to the Health Secretary Wes Streeting urging immediate action. No country has yet implemented all of these measures. The UK could — and should — be the first. Their demands include:

Excerpt from the cross-party letter to the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Wes Streeting, dated 22nd July 2025. Source: Full letter via Jessica Toale MP’s website.

A System Built to Protect Profit, Not People

The legacy of DES reveals how regulation failed by design. Throughout its decades-long use, pharmaceutical companies operated with near-total freedom, bolstered by a government unwilling to impose scrutiny. Even after the thalidomide disaster led to the creation of safety committees, DES was never re-evaluated with the urgency those reforms promised. There was no public inquiry. No recall. No robust tracking of harm. And no accountability. Instead, the institutions meant to protect public health functioned as shields for corporate interests. Regulation was not absent by accident — it was omitted by design to protect corporate interests.

A Reckoning Long Overdue

As survivor testimony grows louder and the political conversation heats up, the UK government must not repeat history by delaying action. A formal inquiry, a national compensation fund, and a screening programme are not generous gestures — they are necessities. They are the bare minimum for restoring trust and addressing harm. To ignore these calls now would not just be political inaction — it would mark the continuation of systemic regulatory breakdown. DES survivors deserve more than promises. They deserve justice.

What You Can Do

As of 22nd July 2025, 36 MPs have signed the cross-party letter. That means 614 had not.

You can help pressure Parliament to act. Here’s how:

Step 1: Contact your MP directly - Use Find and contact your MP to send an email or letter. Ask them to support justice for DES survivors in future debates, motions, or inquiries.

Step 2: Share this information -Tell your friends, family, and networks. The more voices raised, the harder for the government to stay silent.

Step 3: Speak out - If you or anyone you know has been affected by this issue or wants to share their experience, contact ITV News at: [email protected].

The more people who come forward, the harder it becomes for the government to look away.

For Those Affected

If you or someone in your family may have been exposed to DES, there are trusted resources available:

- Understand the cancer risks linked to DES — from the U.S. National Cancer Institute

- Check your eligibility for cervical screening via UK Government guidance

- Explore legal support through a UK-based campaign by Broudie Jackson Canter

- Find medical guidance on cervical cancer and breast cancer via the NHS

- If you’re unsure what to do next, use NHS 111 online or speak with your GP

The legacy of DES may span generations — but silence does not have to. The fight for truth, justice, and accountability is growing. The government must decide: will it meet this moment, or continue to fail those it was meant to protect?

Further Reading

If you're interested in reading more about this issue, you may also find this article of interest: The Legacy of Diethylstilbestrol (DES): A Systemic Failure and the Fight for Justice Published via the Harm and Evidence Research Collaborative (HERC) blog, The Open University.

Sharon Hartles is a Member of the Harm and Evidence Research Collaborative at The Open University, a Member of the British Society of Criminology, and is affiliated with the Risky Hormones research project — an international collaboration in partnership with patient groups.