Blog by Brett Crumley, Lecturer in law

This story begins in feudal England and Wales. It is the sixteenth century. The state is struggling to be born and the Tudors are in conflict with the Catholic Church. The Crown wants to bolster its power and reward its supporters. This historic conflict and the laws enacted at that time had a surprising effect on the landscape in which Carols might be sung at Christmas.

In some areas of pre-Reformation England and Wales, the church owned up to one-quarter of the land, in others, two-fifths. This situation was a problem for the crown as it meant lost income from feudal incidents, among other consequences.

One common subject of feudal donations, a way of transferring land to the Catholic Church, was the ‘chantry’. Founders would leave property to build chapels and maintain priests to pray for the souls of founders, their families, and select nobles and clergy. With the right maintenance gift – such as a productive sheep farm – the chantry might continue indefinitely.

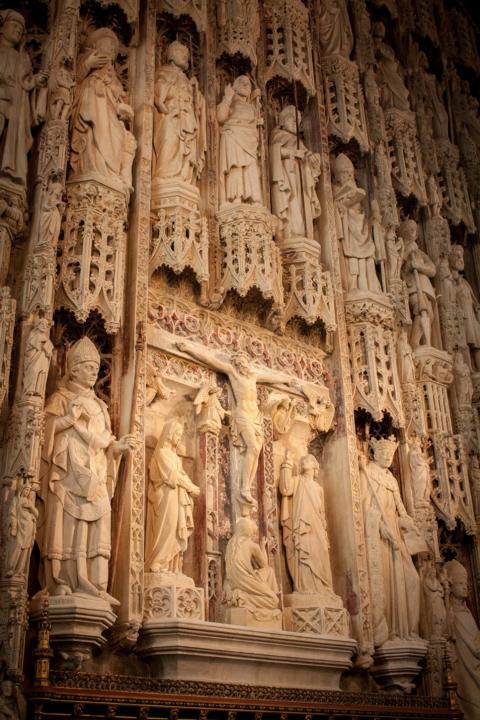

All Souls College, Oxford was founded in 1438 as a college and a chantry. It is rumoured that its founder, Archbishop Henry Chicheley was remorseful for encouraging Henry V to war with France (Cook, 1948, p. 77). The chantry priests were to say masses for those who died in the war as well as for his and King Henry’s souls. The prayers were recited until chantries were dissolved the following century. There is no causal relation but the chantries were dissolved around the same time that Christmas carols were beginning to be published.

In Christmas 1521, the chantry priests of All Souls might have heard joyous singing from across the way at Queen’s College. In that year, Wynkyn de Worde printed the Queen’s College version of the Boar’s Head Carol (Dearmer, Williams, and Shaw, 1969, pp. ix, 39ff). The lyrics celebrate a meal of boar. While the tradition of singing that carol continues, the All Souls chantry and its prayers would not remain for much longer.

Henry VIII and Edward VI enacted a series of mortmain statutes to prevent the church’s land accumulation. The Mortmain Act 1531–32, 23 Henry VIII c 10 banned dispositions of more than twenty years to ‘the use of parish churches, chapels, guilds, brotherhoods, and for obits …’, and chantries. Such legislation was to limit donor’s ability to control the application of property at the expense of the living and, especially, the crown.

The Suppression of Religious Houses Act 1535, 27 Henry VIII c 28 closed the smallest monasteries and religious houses, the property seized. The legislative drafters feared that the heads of those houses would ‘fraudulently and craftily …’ dispose of the property ‘for the maintenance of their detestable lives …’ before the crown’s investigators could complete their surveys. As protection, the statute voided dispositions made in the year up to 1535.

The Dissolution of Monasteries and Abbeys Act 1539, 31 Henry VIII c 13 consolidated the transfer of religious lands surrendered to the crown since the 1535 Act. The newer statute described those earlier surrenders as voluntary. While the truth may have been ‘rather different … this was not open to challenge’ (Baker, 2003, p. 712).

Edward VI continued the dissolution apparently on grounds of religious doctrine, deeming certain gifts and practices superstitious. Intercessory masses for souls in chantries did not align with protestant teaching. His Act whereby certain Chauntries, Colleges, Free Chapels, and the Possessions of the same, be given to the King's Majesty 1546, 1 Edward VI c 14 transferred chantries, colleges, and chapels to the crown.

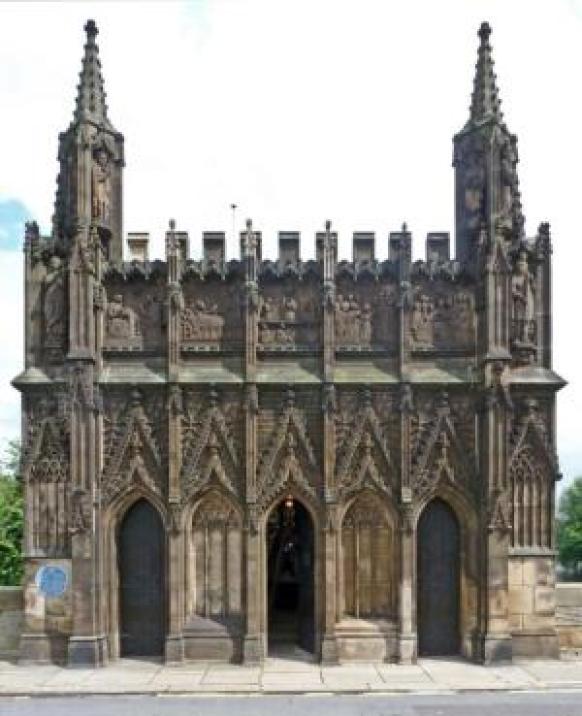

Keith Wrightson called the dissolution the greatest land transfer in England and Wales since the Norman Conquest (Wrightson, 2002, p. 144). Dissolution did not always mean destruction but ex-chantry chapels such as All Souls are now rare. Another exceptional chantry is St Mary the Virgin’s at Wakefield and reportedly survived because it physically supports a bridge. Although the chantry came into disuse, it has been repaired and run as a chapel for some time and hosts Christmas carols at the right time of year.

Photo: Chantry Chapel of St Mary the Virgin, Wakefield

Henry VIII and Edward VI’s mortmain statutes radically shifted the balance of power in England and Wales. As for one of the impacts on Christmas, the Tudor statutes left so few surviving chantries that the remaining ones can be especially impressive venues for Christmas carolling.

References

Baker, J. (2003) ‘Dissolution of the Monasteries’ in The Oxford History of the Laws of England, vol 4, 1483–1558. Oxford: OUP.

Cook, GH. (1948) Mediaeval Chantries and Chantry Chapels. London: Phoenix House Ltd.

Dearmer, P, Williams, RV, and Shaw, M. (1969) Oxford Book of Carols. London: OUP.

Wrightson, K. (2002) Earthly Necessities: Economic Lives in Early Modern Britain, 1470–1750. London: Penguin.

Image Credits

Photo of All Souls College chapel, Oxford, statues in the reredos by Simon Q.

Photo of the Chantry Chapel of St Mary the Virgin, Wakefield, west façade by Tm Green.

Dr Brett Crumley, Lecturer in law, Open University Law School

Contact us

Get in touch with the Open Justice Team