Voluntary Sector ‘Transmission Belts’ in Cross-Sector Collaborations

This blog is written by Dr Daniel Haslam, Lecturer in Management in the Centre for Voluntary Sector Leadership. This was originally written for a series by the Department for Public Leadership and Social Enterprise (PuLSE) and published 1 March 2021.

In recent months several PuLSE blogs have focused on the work of voluntary/non-profit organisations. This post continues that focus on by looking at how the voluntary sector works in cross-sector collaborations, specifically in this case a project with the NHS. An earlier version of this post appeared on the OU Centre for Voluntary Sector Leadership blog and you can read more about the research there.

The project itself – Wellbeing Erewash – was a pilot and part of a general movement towards new ways of working that have now been formalised in the NHS White paper ‘Integration and innovation’. The two key workstreams of the project focussed on (1) increasing personal and community resilience, and (2) the integration of primary and community care. The voluntary sector was primarily involved in workstream (1) which included within it a specific focus on ‘strengthening the voluntary sector’.

With the continued emphasis on the voluntary sector in NHS policy, and seen in responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, it is important to try to understand more about how collaborations between the sectors work in practice. I adapt Albareda’s (2018) concept of ‘transmission belt’ organisations to explain the voluntary sector’s role in Wellbeing Erewash and question some of the wider assumptions about the voluntary sector in public sector policy.

Research Approach

I spent 12 months ‘in the field’ working alongside a voluntary sector organisation which was the ‘named lead’ organisation for the Wellbeing Erewash project. I contributed to various aspects of the project and the organisation during my time there as well as collecting data for my research. That data included field notes, interviews, documents, and other ‘naturally occurring’ data such as meeting minutes and project literature. I analysed the data using a thematic approach (searching for themes within the data) informed by Braun and Clarke (2006).

Findings

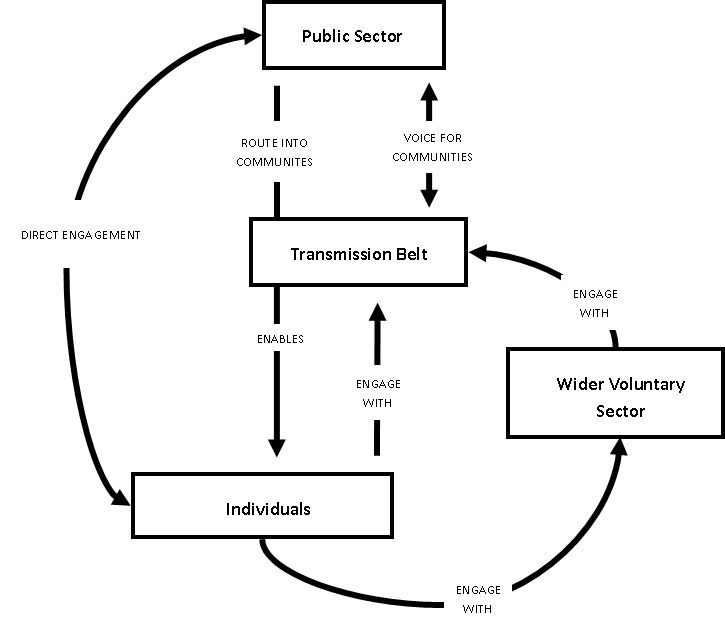

I found that the voluntary sector was used within the project in two distinct ways. Firstly, as a ‘route in’ to communities and secondly as a ‘voice for’ them.

A ‘route in’

The ‘route in’ aspect of the role involved hosting meetings, events, workshops, and forums designed to both enable the project to have access to a wider range of voices and for individuals within the community to have an opportunity to feed into the project and have their ‘say’. Unfortunately, these events were largely unsuccessful in their goal of increasing involvement and had very little direct engagement from individuals. This was the result of a range of factors related to both the individual organisations involved and aspects of the collaborative project, including a lack of resources, time, commitment, and staff skills. For example, although the voluntary sector acted as the ‘host’ for the two initial ‘community engagement events’ for the project there was no resource given to the organisation that was carrying out that role or a specific responsibility identified for any organisation to continue to engage in that way. It was also unclear how any additional individuals who wanted to engage would be able to do so as no formal structures existed to enable that to happen.

A ‘voice for’

The ‘voice for’ aspect was visible in the project planning meetings in which a representative was invited to give a voluntary sector and/or community perspective. This happened despite both voluntary sector and NHS workers pointing out in those same meetings that no single person or organisation was able in reality to represent the diversity involved. However, acknowledging that reality did not stop voluntary sector representatives being used in this exact way. Unfortunately, the voluntary sector was not granted a place on the highest level ‘leadership’ meetings in which important decisions were made about the project and were also not a ‘named partner’ on project literature. It was not entirely clear if this was a deliberate exclusion or merely an oversight. However it meant that although there seemed to be a preference for the ‘voice for’ role in practice it was itself almost impossible to carry out effectively.

The Transmission Belt

The findings of this research, from within the context of a cross-sector collaborative project aimed at the delivery of services, echo those of Albareda (2018) from the very different context of international policy development. Albareda’s work focussed on the role of voluntary sector organisations in the development of policy across the EU. They emphasise a role for the sector to both ‘boost diverse participation’ and ‘produce a consistent message’ for policy makers. They use the term ‘transmission belt’ to describe this twin role and suggest that the majority of voluntary sector organisations are not able to achieve the ‘ideal type’ assumed to exist by the public sector because of organisational issues (such as capacity, funding, etc.) and because of the conflicting demands across the two aspects of the role -attempts to boost diverse participation come at the expense of the ability to provide a consistent message to policy makers

As Albareda’s work involved the statistical analysis of survey data to generate these broad concepts it is not able to provide insight into how the transmission belt role works in practice. In contrast, the methodology of my research, being qualitative and focussed on uncovering underlying processes, is better able to represent this detail from practice.

Table 1 (below) shows how my findings relate to Albareda’s twin demands.

| Albareda (2018) – twin demands placed on ‘transmission belt’ organisations in policy | How organisations enact this in practice within cross-sector collaborations |

|---|---|

| Boosting Diverse Participation | Acting as a ‘Route Into’ communities |

| Producing a Consistent Message | Acting as a ‘Voice For’ communities |

Figure 1 (below) represents how the transmission belt role worked and interacted with other aspects of the Wellbeing Erewash project including individual citizens and the wider voluntary sector.

So What?

Like much academic research the key question to be asked is what value this has both to practitioners and to the development of understanding about the concepts and issues involved. This research contributes in several different ways.

Firstly, it leads to a greater understanding of the role of the voluntary sector in cross-sector collaborations. As these ways of working are only set to increase this is particularly important. Of particular note is how much of the public sector policy that leads to the involvement of the voluntary sector appears to be based on assumptions about the way the sector works (and is able to work) which, as previous research has pointed out, lack evidence (Locke et al., 2001; Fleming and Osborne, 2019; Mazzei et al., 2020).

Secondly, the research challenges policymakers to interrogate their assumptions about the voluntary sector, community engagement, and how collaboration works in practice. It also challenges the voluntary sector to consider their own role and whether their actions work to support these assumptions and/or maintain an ideal about the sector which is impossible to achieve.

Thirdly, attempting to conform to this role risks damaging relationships between service users, communities, and voluntary sector organisations, not least because of the conflict between the two aspects of the role.

Finally, this research emphasises that in order to carry out either aspect of working with communities – acting as a ‘route in’ or a ‘voice for’ – or attempting to deliver both, requires appropriate resourcing in relation to organisational funding, staff training, trust, power, and control.

Further Reading

Department for Health and Social Care (2021) Working together to improve health and social care for all. Policy Paper.

Haslam, D. (2019) The Role of the Voluntary Sector in Cross-Sector Collaboration. Centre for Voluntary Sector Leadership Blog.

NHS Confederation (2017) New Models of Care in Practice: Wellbeing Erewash.

References

Albareda, A. (2018) 'Connecting Society and Policymakers? Conceptualizing and Measuring the Capacity of Civil Society Organizations to Act as Transmission Belts', Voluntas, Vol. 29, pp.1216-1232.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006) 'Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology', Qualitative Research in Psychology, vol.3, no.2 pp.77-101.

Fleming, S. S. & Osborne, S. (2019) 'The Dynamics of Co-Production in the Context of Social Care Personalisation: Testing Theory and Practice in a Scottish Context', Journal of Social Policy, Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 671-697.

Locke, M., Robson, P., & Howlett, S. (2001) 'Users: At the Centre or the Sidelines?', in Harris, M. and Rochester, C. (2001) (eds) Voluntary Organisations and Social Policy in Britain: Perspectives on Change and Choice, Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 199-212.

Mazzei, M., Teasdale, S., Calo, F. & Roy, M. (2019) 'Co-production and the Third Sector: Conceptualising Different Approaches to Service User Involvement', Public Management Review, Vol. 22, No. 9, pp. 1265-1283.