Stuff you were afraid to ask about hi-tech clusters

Ian Reid

From California’s ‘Silicon Valley’ to the UK’s ‘Cambridge phenomenon’, hi-tech clusters are held up as ‘machines’ for commercialisation, turning Research and Development (R&D) into economic success. The attraction for policymakers seems obvious, but is it really that simple?

What’s meant by ‘hi-tech cluster’? An industrial cluster is a geographic concentration of inter-connected companies and institutions in a particular field that compete and cooperate (Porter, 1998). The technologies underpinning this will be ‘hi-tech’ if they are cutting edge, utilising recent advances in scientific knowledge, methods, and materials.

My interest in high-tech clusters traces back to an early career conference in Silicon Valley. As a physicist with a passion for technology, I was struck by the unique dynamics of this celebrated California cluster of hi-tech innovation hub. While personal experience sparked my curiosity, the broader implications of how these clusters function offer insights relevant to anyone interested in hi-tech innovation and economic development.

A significant tradition in the literature contends that successful clusters develop organically through chance and path-dependency, rather than strategic intervention (mostly top-down planning). This perspective questions whether governments can successfully engineer hi-tech innovation hubs, pointing to examples like London's 'Tech City,' which has produced questionable results.

Duranton (2011), a critical researcher in this field of study has questioned the theoretical underpinnings and supporting evidence for realisable economic benefits. There are concerns that cluster initiatives may lead to zero-sum competition between regions for limited investment funds. Yet everywhere we continue to see significant policymakers’ effort, public money – our taxes – and political capital invested in trying to do just that. For the latest ‘fashions’ in cluster policy see the UK’s Industrial Strategy.

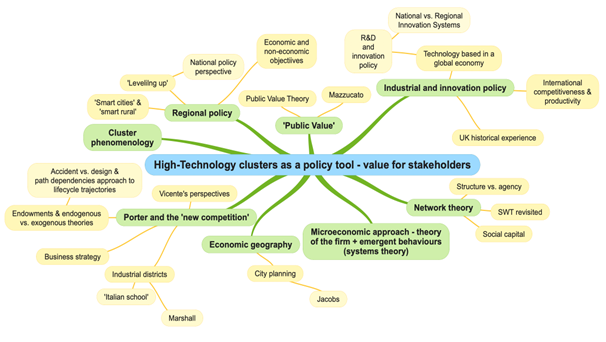

I am now in year 2 of a part time PhD in Economics at The Open University, exploring some of these ideas. This blog draws on my ongoing PhD and gives a summary of my progress to date. The ‘map’ below, while not expecting you to digest all the details, it should give a sense of the breadth and complexity of the interconnected, multi-disciplinary, cluster literature.

Author’s own figure

The historical sweep ranges from the famous economist Alfred Marshall’s observations on industrial districts during the Industrial Revolution to latest thinking on social networking analysis (SNA) (Breschi and Malerba, 2005). From scale economies and the importance of geographical proximity for transferring tacit knowledge, to social constructs and behavioural science. From the purely descriptive to mathematical modelling, taking in institutional economics, policy and public value, and the codification of knowledge along the way.

Michael Porter’s influential work, drawing on microeconomic concepts, positions clusters as drivers of firm competitiveness (Huggins and Izushi, 2011). A wellspring for policymakers’ interest, now reflected in the policy literature. But focus is on policy tools for ‘cluster management’, rather than clusters as tools for policy.

Theory-wise, I also considered an alternative approach of New Economic Geography (NEG). This draws on social science, SNA and game theory, interpreting economic processes through spatial patterns, networks and across geographical scales (Coe et al., 2019). NEG versus Porterian traditions remain an open debate, with issues like congestion costs in clusters consistently underplayed.

Unresolved issues include how to define cluster boundaries, through the role of endowments, to path dependencies. Duranton challenges how long-term cluster benefits can be realised across different geographical scales, posing questions for their role in innovation and industrial policy. A comprehensive, holistic view of stakeholding and how cluster benefits are captured is also lacking in the literature.

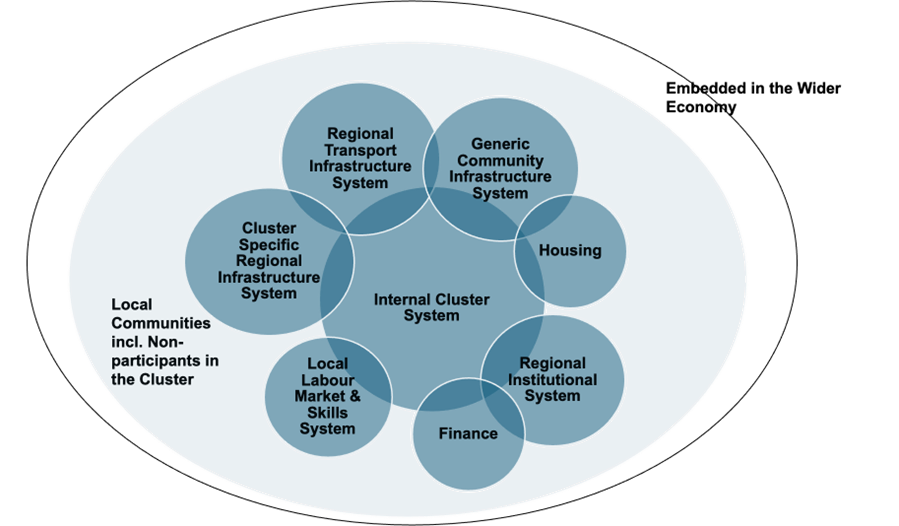

My main research question emerged as ‘How can hi-tech clusters within regional innovation systems be assessed as a public policy tool in theory and practice?’. Supplemental questions explore the nature of stakeholding – how different stakeholders anticipate, realise and trade-off cluster benefits and costs. This leads to a system-of-systems overarching conceptual framework, as shown below.

Author’s own figure

This underpins the overall design of a mixed-methods research methodology, utilising several specific methods. Unstructured initial interviews with key informants in the subject clusters are used to inform the scope of quantitative desktop research, utilising secondary sources. This will inform development of a survey, with subsequent statistical analysis of returns and follow-up semi-structured interviews across a wide range of stakeholder types, exploring topics emerging during thematic analysis. Focus groups will be used to probe stakeholder interactions.

Since writing this blog, data collection has started. The South Wales compound semiconductor cluster and Scotland’s ‘critical technologies supercluster’ are targets for study, with initial interviews conducted with a senior policymaker and industry representative in each. I am currently selecting a third, English, cluster. The analysis and synthesis phase will develop a set of interlocking case studies, comparative between geographies.

This research will systematise an approach to costs and benefits, beyond just economic, across a broad stakeholder landscape. This includes those within the region, not directly engaged in the cluster, but negatively impacted by congestion costs while seeing limited benefits. A key output will be bottom-up development of a practical, empirically informed, holistic assessment framework for clusters as tools for policy in both theory and practice. This will support regional policymakers in assessing existing clusters and options for future initiatives, in the context of their policy objectives and broader constituencies they serve.

It is interesting to speculate on what might be uncovered about public value from clusters and their role in innovation systems and associated policy. Or how policymakers might intervene to enhance value capture in regional or national economies. For now, I hope this piqued your interest and, if so, feel free to get in touch https://fass.open.ac.uk/economics/phd-student/ian-reid or https://www.linkedin.com/in/ipreid/

References

Breschi, S. and Malerba, F. (eds.) (2005) Clusters, Networks, and Innovation. Reprint, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Coe, N., Kelly, P., and Young, H. (2019) Economic Geography: A Contemporary Introduction. 3rd edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Duranton, G. (2011) California Dreamin’: The Feeble Case for Cluster Policies. Review of Economic Analysis 3 (2011) pp. 3-45.

Huggins, R. and Izushi, H. (eds.) (2011) Competition, Competitive Advantage, and Clusters: The Ideas of Michael Porter. Reprint, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Porter, M. (1998) Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. Harvard Business Review. November-December 1998. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Publishing.

Share this page:

Contact us

To find out more about our work, or to discuss a potential project, please contact:

International Development Research Office

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0)1908 858502

E: [email protected]

.jpg)